Ultimate Guide To 2018 Meteor Showers & How To Photograph Them

What a year 2017 has been, several meteor showers put on impressive displays this year, combined with the US solar eclipse made for a very exciting year for Astrophotography and star gazing as a whole. If you have missed out on much of this action fear not, for 2018 promises to bring in some equally impressive displays. In this guide you will find the major Meteor displays that are on their way for 2018 and how to photograph them with your camera.

So what does 2018 have in store for us? Lets find out.

- Introduction

- Shooting Stars

- Meteor Showers

- -- January: Quandrantids Meteor Shower

- -- April: Lyrid Meteor Shower

- -- May: Eta Aquarids

- -- August: Perseids

- -- October: Draconids

- -- October: Orionids

- -- November: Taurids

- -- November: Leonids

- -- December: Geminids

- -- December: Ursids

- Camera Settings

- Shooting Locations

- UK's 17 Dark Sky Discovery Sites

- Tips & Tricks

Shooting Stars

A shooting star has nothing at all to do with a star, however is a common term used around the world to describe in simple and perhaps romantic terms tiny bits of dust and rock called meteoroids falling into the Earth's atmosphere and burning up.

The short-lived trail of light and the often rapid burning meteoroid is called a meteor.

Throughout any given year, you are likely to see a great number of meteors in the night sky. These events are called meteor showers and they occur when the Earth passes through the trail of debris left by a comet as the earth orbits the Sun. These meteor showers are given names based on the constellation present in the sky from which they appear to radiate. For example, the Leonid Meteor Shower annually in November each year, or Leonids, appear to originate in the constellation Leo.

It is important to understand that the meteoroids (and therefore the meteors) do not physically originate from the constellations or any of the stars in the constellations, but just appear to be travelling away from that point in the heavens because of the way the Earth encounters the specks of dust and rock whilst moving in the path of the comet's orbit/passage. Associating, the shower name with the region of the sky they seem to come from just helps astronomers, astrophotographers and star gazers know where to look!

Did you also know, a meteoroid is a small rocky or metallic body in outer space. Meteoroids are significantly smaller than asteroids, and range in size from small grains to 1 meter-wide objects. If by chance any part of the meteoroid survives burning up as it enters the earth's atmosphere and actually hits the Earth, that remaining bit is then called a meteorite.

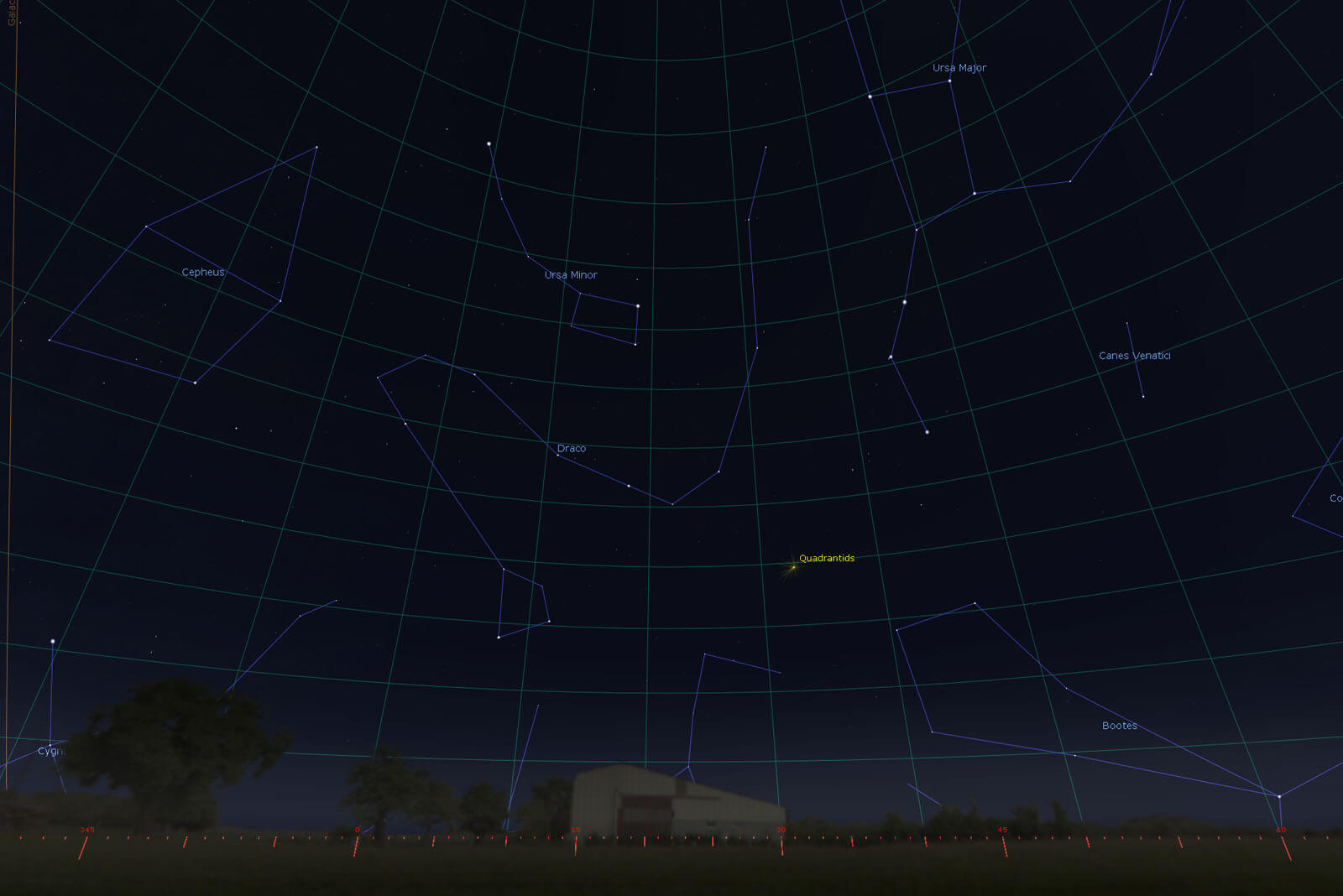

Quandrantids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 3rd/4th January 2018

The Quadrantids generally sees the transition between the end of December and the second week of January.It typically peaks around January 3 to January 4 and is most active in a relatively short space of time the evening of the 3rd until the early hours of the 4th, unfortunately this year a full Moon will make it difficult to see some of the smaller and fainter meteors as they streak across the sky, but you should still be able to see the brighter ones with the Naked eye. Due to the full moon watch out for over exposure when trying to photograph them.

Quandrantids History

Quadrans Muralis (Latin for mural quadrant) was a constellation created by the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande in 1795. It was between the constellations of Boötes and Draco, near the tail of Ursa Major containing stars between β Bootis and η Ursae Majoris (Alkaid).

Johann Elert Bode converted its name to Latin as Quadrans Muralis and shrank the constellation a little in his 1801 Uranographia star atlas, to avoid it clashing with neighbouring constellations. The constellation was left off a list of constellations drawn out by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1922. The Quadrantids is also sometimes called Bootids after the modern constellation, Boötes and are often associated with an asteroid - the 2003 EH1. The asteroid takes about 5.5 years to orbit around the Sun.

Where to look

Look towards the The Big Dipper (US) or the Plough (UK) which consists of seven bright stars of the constellation Ursa Major the point of origin should then be down and left a little from the plough. While it is not necessary to look in a particular direction to enjoy a meteor shower, I would suggest suggest lying down on the ground looking towards the North and look at the sky above you to view the Quadrantids.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesLyrids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 22nd/23rd April 2018

This year, the Lyrids are expected to peak on April 22nd and 23rd. A First Quarter Moon on those dates will hamper the show a little causing the faintest of meteors difficult to see, however to the accustomed eye and in a dark skies area the viewing should still be good. While the April Lyrids are not as plentiful as some other annual meteor displays, these shooting stars tend to be bright and fairly fast.

Lyrids History

The Lyrid meteors are remnants of the dust and particles left behind from Comet Thatcher first discovered in April 28, 1861 but truly understood until after 1833, when a tremendous "storm" of meteors — the Leonids — took place. The annual November Leonids shower led professor Edmond Weiss of Vienna in 1867 to suggest and later that year Johann Gottfried Galle of Germany to later prove, the link between the passing of comet Thatcher and the annual meteorite display in April. Because the meteors appear to originate from a spot in the sky not far from the blue star Vega, in the constellation of Lyra, "the lyre," they are known today as the Lyrids.

Where to look

Considered to be the oldest known meteor shower, the Lyrids are named after constellation Lyra. The radiant point of the shower, this point, lies near the star Vega, one of the brightest stars in the sky during this time of the year. A good view of the east horizon should provide a good viewing and photography experience. The best time to see shooting stars from the Lyrids is after nightfall and before dawn.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesEta Aquarids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 6th/7th May 2018

The Eta Aquarid meteor shower is usually active between April 19 and May 28 every year. For 2018 it is predicted that the peak of the meteor shower should happen on the 6th of May with the early morning before dawn being the best time to capture them on camera.

Eta Aquarids History

The Eta Aquarids is one of two meteor showers created by debris from Comet Halley. The other is the Orinids Meteor Shower in October as the Earth passes through Halley's path around the Sun twice in any given year.

Unlike most major annual meteor showers, there is no sharp peak of activity, rather, a good rate of meteorites can be expected approximately for one week centred on May 6th so viewing before the 6th and after for a short while could lead to some impressive 'shooting stars'.

Although this shower is not as spectacular as say the the Leonids, it is not an event to be missed. The Eta Aquariids get their name because their radiant appears to lie in the constellation Aquarius, near one of the constellation's brightest stars, Eta Aquarii.

Where to look

The Eta Aquarids seem to radiate from the direction of the constellation Aquarius in the sky. So look for that constellation in the early hours pre-dawn for the best chance of seeing the meteors streaking across the sky. The Meteor display should be visible from any location on earth as long as the weather is permitting of course.

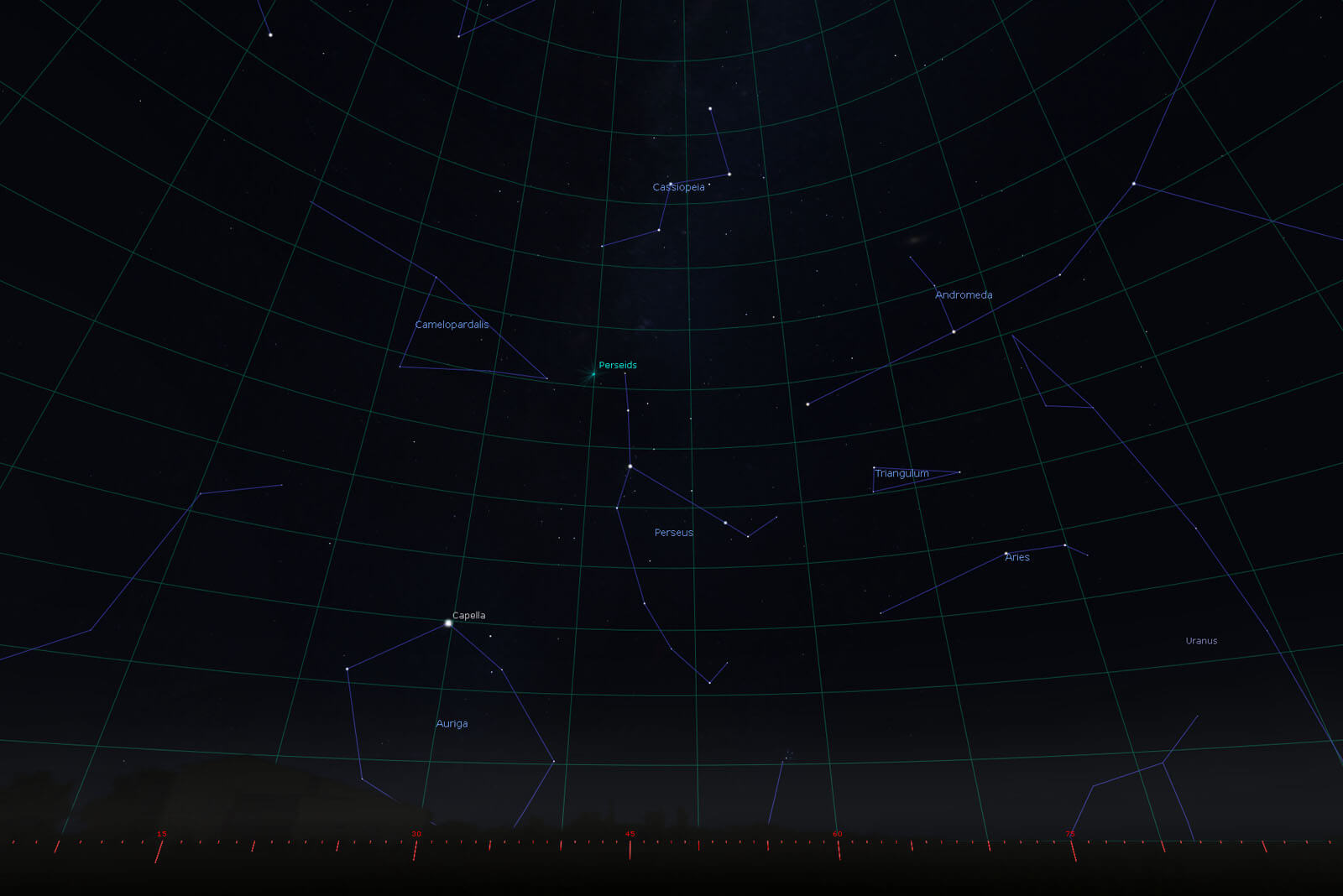

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Perseids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 12th/13th Aug 2018

The Perseids will peak on the night of August 12 and early morning hours of August 13. In addition a New Moon will create very dark skies and excellent conditions to see the shooting stars. Being one of the brighter meteor showers of the year, and occurring every year between July 17th and August 24th. The best time to view the Perseids, and most other meteor showers, is when the sky is the darkest. Depending on the Moon’s phase from year to year, most astronomers suggest that the best time to view meteor showers is right before dawn. During at its peak, you can expect to see between 60 to 100 meteors in an hour from a dark location

Perseids History

Made from the tiny space debris left by the passing comet Swift-Tuttle, the Perseids are named after the constellation Perseus. This is because the direction, or radiant, from which the shower seems to come in the sky lies in the same direction as the constellation Perseus.

In 1835, Adolphe Quetelet identified the shower as emanating from the constellation Perseus. In 1866, after the perihelion passage of Swift-Tuttle in 1862, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli discovered the link between meteor showers and comets. This finding and connection is noted in an exchange of letters between Giovanni Virginio and Angelo Secchi.

As an aside; Some Catholics refer to the Perseids as the "tears of Saint Lawrence", suspended in the sky but returning to earth once a year on August 10, the canonical date of that saint's martyrdom in 258 AD. The saint is said to have been burned alive on a gridiron, this event is suspected to be the origin of the legend and tale that the shooting stars of Perseids are the are the sparks of that fire and that during the night of August 9th & 10th its cooled embers appear in the ground under plants, and which are known as the "coal of Saint Lawrence"

Where to look

The Perseids can be easily seen in the Northern Hemisphere. Try looking to the north-east part of the sky, and the zenith (the point in the sky directly above you) for the best views. You may even be looking to witness an 'Earth-grazer'.

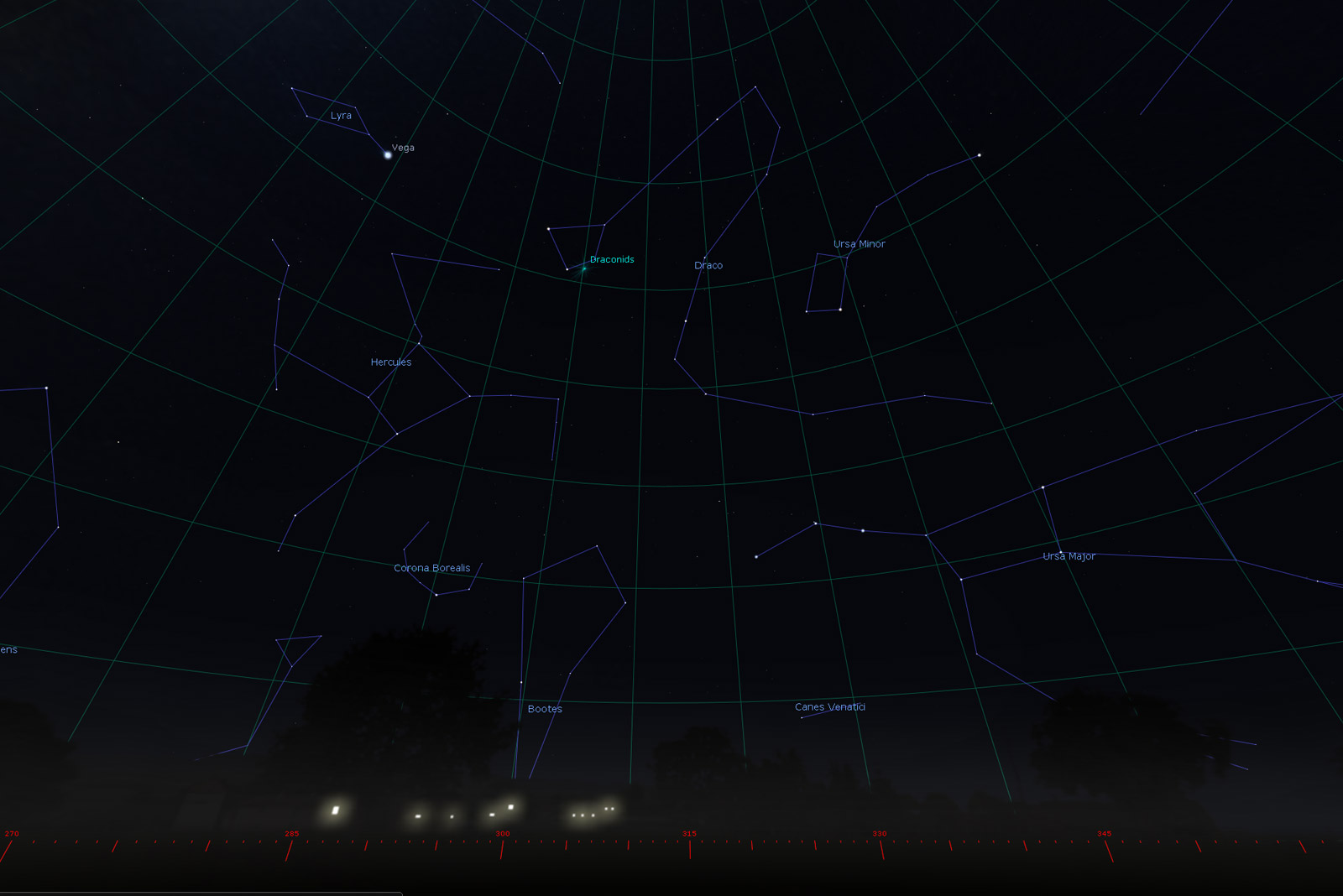

Back to Meteor Shower DatesDraconid Meteor Shower - Peaks > 8th Oct 2018

October 2018 is a great month to see a meteor shower for the month has two events that well worth braving the cooler nights for, starting at the beginning of the month the Draconid meteor shower, also sometimes known as the Giacobinids is expected to reach its peak on October 8. A new Moon will allow viewers to easily see the shooting stars and with a little bit of luck the weather will also be good on this night.

The Draconids owe their name to the constellation Draco the Dragon, and are created when the Earth passes through the dust debris left by comet 21 P/ Giacobini-Zinner. Although the Draconids have been responsible for some of the most spectacular meteor showers in recorded history, most recently in 2011

Draconid History

This annual meteor shower results when the Earth in its orbit crosses the orbital path of Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner. This comet has an orbital period of about 6.6 years. Most meteors in annual showers are generally names after the constellation they appearer to radiate from as the earth passes through the debris left behind, Draco’s meteors however, defy convention by sometimes also being called the Giacobinids, this is a nod of honour and appreciation for Michel Giacobini who discovered this comet on December 20, 1900.

An earlier sighting way back in 1913 added Zinner to the comets name, which thus the comet became known as 21P Giacobini-Zinner.

The Draconid meteor shower has produced some fantastic and some would say even awesome meteor displays in 1933 and 1946, with thousands of meteors per hour being seen in those years. In October 2011, European observers and photographers saw over 600 meteors per hour! So you never know 2018 might be a good year :)

An account of the stunning meteor storm of 1933. can be found at the Astronomy Abstract Service from the Smithsonian and NASA The Meteors from Giacobini’s Comet by C.C. Wylie.

Where to look

Stargazing from Northern America, Europe and Asia are the best locations in order to watch the Draconid Meteor Shower, those closer to the Equator and those in the southern hemisphere can still see the shower, but its more tricky to do so due to the radiant position in the night sky, where by the constellation of Draco barely clears the horizon.

While it is not necessary to look in a particular direction to enjoy the Draconid meteor shower, try to shoot in the direction of the stars Eltanin and Rastaban which are the two brightest in the Draco constellation during the early evening.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Orinids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 21st Oct 2018

The Orionids is the second meteor shower in October. It usually peaks around the evening of the 21st October and into the early hours of the 22nd. In 2018, the Orionid meteor shower will be visible from October 2nd to November 7th. On some occasions, up to 20 meteors are visible every hour. The Orionid meteors that streak across the sky are some of the fastest and brightest among meteor showers, because the Earth is hitting a stream of particles almost head on, so you could get an 'Earth-grazer' or perhaps two if you are very lucky.

The Orionid meteor shower is 1 of 2 meteor showers created by debris left over from Comet Halley. The Eta Aquarids in May is the second meteor shower. As a note, Comet Halley, takes around 76 years to go round the sun, so the next time we will be able to see it from the earth will be in 2061!

Orionid History

The Orionids are named after the direction from which they appear to radiate, which is near the constellation Orion (The Hunter). Reports of the Orionids the resulting Meteor shower from Comet Haley, did not first appear until 1839 when an American in Connecticut spotted the shower. Observations of the shower were then subsequently recorded during the American Civil War between 1861 and 1865.

As per the Eta Aquarids, The Orionids are a direct result of the earth passing through the debris stream of Comet Halley (for a second time in a year). Records of Halley's Comet passing date back as far back as 240 B.C. but until quite recently no one realized that the same comet was making multiple appearances in the night sky at a regular interval of 75 years.

By 1705, then-University of Oxford professor and astronomer Edmund Halley published "Synopsis Astronomia Cometicae" ("A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets"), which showed the first evidence that the comet is reoccurring.The historical records of a comet that appeared in 1456, 1531, 1607 and 1682, was used by Halley to calculate that it was in fact the same comet and prediction of it reappearing 1758 was made. Unfortunately Halley died before the comet's return, however his schedule for its next appearance was on the mark and in 1758 the comet was once again observed. Due to this, the comet was named after Halley in honour for his discovery.

Where to Look

The best time to view the Orionids is just after midnight and right before dawn. This year a first quarter moon will really help with the stargazing and photography and due to the radiant point being that of Orion (the Hunter), one of the most easily located and recognisable constellations in the night sky. Pointing your camera in this general direction should yield a capture of two.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Taurids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 5th Nov 2018

The Taurids is an annual minor meteor shower an one of two in November peaking on the 5th with an average between 5 and 10 meteors per hour. Although the rate is low the Taurids often produce bright and spectacular fireballs. In addition, the Taurids are unusual in that the Meteor shower consists of two separate debris streams. The first debris stream made up of dust grains left behind by Asteroid 2004 TG10. The second debris stream is left behind by ice and rock particles from Comet 2P Encke. This particular meteor shower runs annually from September 7th to December 10th

Taurids History

The Taurids in the northern hemisphere come from Comet Encke, a short-term periodic comet that orbits the sun about once every 3.3 years. It was first spotted by Pierre Mechain in 1786 and was first recognized as a periodic comet in the 1800's by Johann Franz Encke. In the southern hemisphere the meteor shower is provided by the debris left behind Asteroid 2004 TG10

Where to Look

The thin crescent moon will set early in the evening of the 5th November leaving dark skies for viewing. Best viewing will be just after midnight and just before dawn from a dark location far away from city lights and hopefully fireworks displays and raging bonfires (in the UK). The Meteors will appear to typically radiate from the constellation Taurus. To find Taurus, look for the constellation Orion and then peer to the north-east to find the red star Aldebaran, the star in the bull's eye. If you look in this general direction you should easily catch a glimpse of a shooting Taurid.

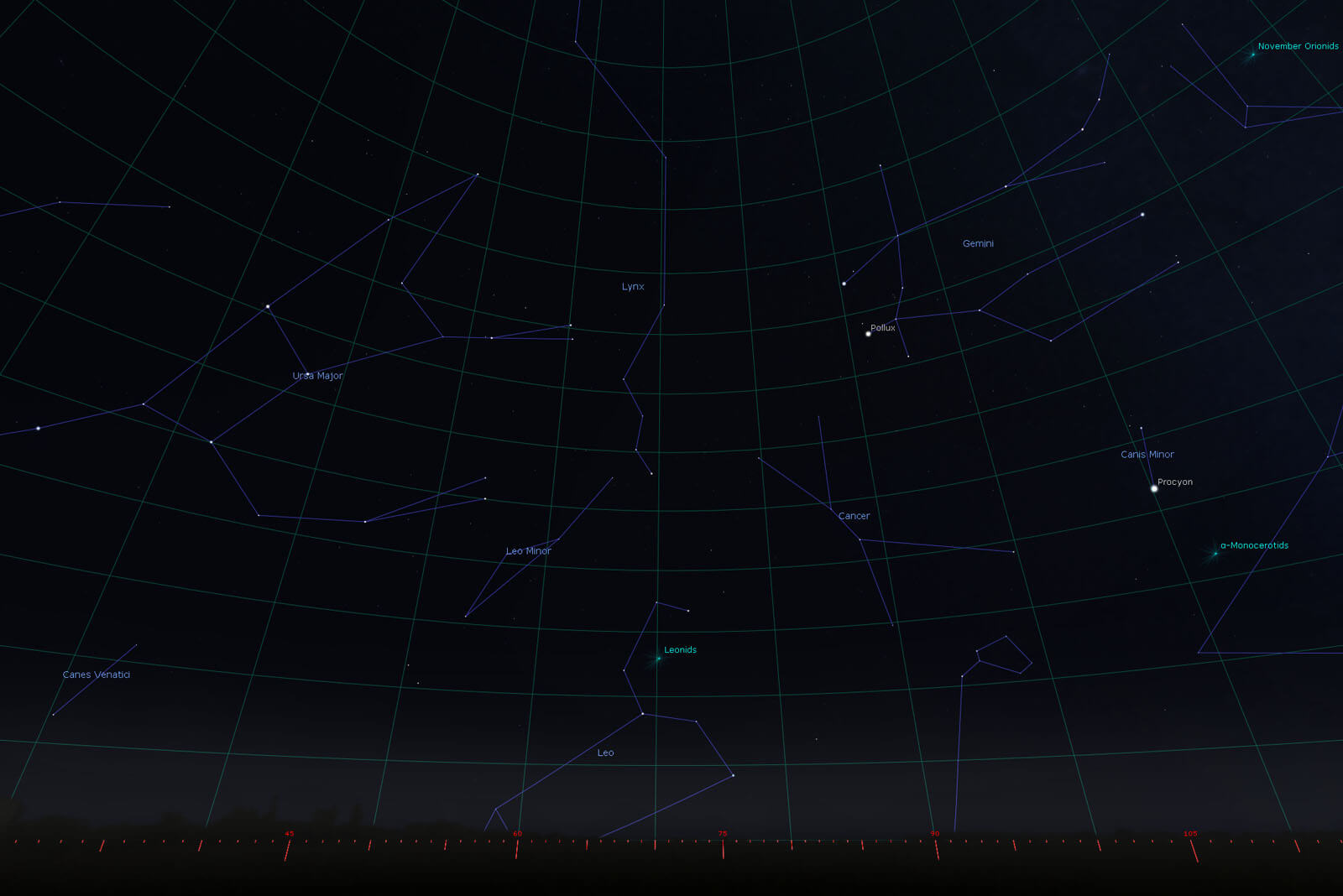

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Leonids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 17th/18th Nov 2018

The Leonids is an average Meteor shower, often producing up to 10-15 meteors per hour at its peak. The Leonids are unique in that it has a cyclonic peak about every 33 years where hundreds of meteors per hour can be seen.That last of these occurred in 2001. So 2034 should be a date in your diary

Leonids History

The Leonid Meteors are produced by dust and debris left behind by comet Tempel-Tuttle, which was discovered in 1865. This year the Meteor shower peaks during the night of the 17th and morning of the 18th of November. The Meteor shower runs annually from the 6th November to the 30th of November each year. In November 2018 a waxing gibbous moon will set shortly after midnight leaving fairly dark skies for what could be a good early morning show on the 18th.

Where to Look

The Leonids can be seen by viewers from both hemispheres. The Leonids appear to radiate out from the constellation of Leo. you should be able to see the best shooting stars by looking at the night sky directly above and to the east. Be sure to allow plenty of time to allow your eyes to adjust to the relative darkness for the best viewing experience.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Geminids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 13th/14th Dec 2018

The Geminids to many is the best and most impressive of the meteor showers. The reason is simple, on average this particular meteor shower produces up to 120 multicoloured meteors per hour at its peak on the 13th and 14th of December, however there is lots of activity generally in the nights building up from the 7th December and afterwards until the 17th of December, so if poor weather gets in the way you should still get a good chance of seeing this event on one of those other nights.

Geminids History

Unlike most other meteor showers the Geminids are produced by dirt and debris left behind by an asteroid named 3200 Phaethon and not a comet. This asteroid was first discovered in 1982 and takes about 1.4 years to orbit our Sun. In 2018, the Geminids Meteor shower will peak on the night of the 13th December and morning of the 14th December as the earth passes through the debris field left behind.

Where to Look

The Geminds Meteors appear to radiate from the constellation Gemini and should be viewable from all parts of the globe, weather permitting. with the best viewing done in a southerly direction, so try to get clear views to the southern horizon for the best chances of seeing this display. An added benefit this year is that the first quarter moon will set shortly after midnight leaving dark skies for what should be an excellent early morning show.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesThe Ursids Meteor Shower - Peaks > 21st/22nd Dec 2018

The Ursids is another minor meteor shower producing on avg only about 5-10 meteors per hour. Still it makes for a fitting end to busy year of stargazing. The shower runs annually from December 17-25. It peaks this year on the the night of the 21st December 2018 and morning of the 22nd December 2018.

Ursids History

The Ursids are produced by dust and rock grains left behind by the comet, 8P/Tuttle, also sometimes known as Mechain-Tuttle's Comet, which was first discovered in 1790.

Where to Look

This year the glare from the full moon will hide all but the brightest meteors, and the The Ursids can only be seen from the Northern Hemisphere. However if you are patient and the weather is kind you may still be able to glimpse a meteor or two radiating from the constellation Ursa Minor.

Back to Meteor Shower DatesCamera Settings

You don't need to have an all signing and all dancing super expensive camera to photograph one of the many Meteor showers in 2018, a reliable DSLR/mirrorless/bridge camera with a wide angle lens and a tripod should be all you need. More importantly than the equipment; in my opinion, is the location in which you choose to shoot from. I try to be in an area with little to no light pollution, remote coastal regions are often good, or remote rural locations. I also try to choose a location with a clear view to the horizon in which the Meteor shower your trying to photograph radiant point is located, and if I want something a little more interesting try to find monument, building or a landscape feature that will provide an interesting foreground subject to really add that extra ingredient to your image. As for the best settings to use, the following should guide should get you into the right area to get a decent shot! You may need to experiment a little, and capturing a good shot is as much down to timing and luck than having the perfect settings, but the more you try the better the chances of capturing something special.

Aperture - A wide open aperture will allow more light to enter your camera. f/2.8 is perfect for astrophotography, with f/4 is being more than adequate. Some people may opt to go as high as f/1.8 however from experience f/2.8 is just fine and is my recommendation if your lens can support it. This is due to the trade off between the amount light collected against the sharpness of the resulting image. f/2.8 to f/4.0 strikes a good balance between these to variables.

Shutter Speed - Typically 20-30 secs. Although dependent on your Camera position to the Celestial equator you may need to reduce this to 10-20 secs for sharp background stars. If you want to capture the background stars trailing in your image then a shutter speed of 60 to 300 seconds would be more suitable. It's not unheard of for people to expose a shot for 3 or 4 minutes or do multiple exposures of 45+ seconds and blend in post production when trying to create long star trails. The challenge of capturing a shooting stars however is to keep all other stars being relatively static/sharp in the image. This is where a well known astro-photographic rule 'The 500 Rule' comes into play, more on that in a bit. All in all, the desired outcome of the image is one that you want to produce though, so you have a couple of options in how you decide to handle the shutter speed

ISO - You'll need your cameras sensor to be a little more sensitive to light that is hitting the sensor than you would during the day, at night the lack of light means ISO value of 1600/3200 is generally perfect for short exposure astrophotography. If your camera can handle low-light high-ISO without too much noise being also captured in the resulting image then you may want to push the ISO up from 3200 to 6400, typically this does reduce the resulting image quality, but today's camera technology does see some cameras being able to go as high as 12800 and above with little to no noise and image degradation. Generally though ISO of 1600/3200 will be about right for the vast majority of camera owners.

Focal Length - Use your widest lens that you have, that is 14mm rather than 75mm, although, you can photograph the night sky with a telephoto lens, the objective here is to capture a shooting star, or if your lucky an earth grazer rather then a deep space object like Nebula, Galaxies or Magellanic Clouds. With a telephoto lens your field of view is greatly reduced so capturing a shooting star through a small field of view is much less likely. (I typically shoot at around 14/15mm on a Pentax K1 full-frame camera). A wide focal length will allow you to capture as much of the night sky as possible and improve your chances of capturing the meteors as they streak and burn up high above your head. In addition to this, a wider focal length typically allows more light to reach the sensor on your camera which is far better for shorter shutter exposures and also benefits your ISO choice above.

* Achieving Sharp Stars with the '500' Rule

As eluded to previously, if you want to capture really sharp stars with little to no visible star trailing then the '500 Rule' might be for you, in essence, limiting the shutter time with the 500 Rule helps reduce star trailing while also allowing adequate light to enter the lens. Ok, so how do you use it, well, let's say you're taking a shot with a 24mm lens on a full frame camera. 500 / 24 = 21 seconds, which you can round down to 20 seconds of exposure time.

To break that down, 500 divided by the focal length of your camera in this case 24mm will give you 21 seconds of exposure time before you will notice the stars in your images start to trail. I always like to round this down by one second just to be sure.

If you are using an APS-C Sensor (Crop Frame) camera the Math is a little different. A full frame camera has a crop factor of 1x, but APS-C sensors have either 1.5x or 1.6x depending on the manufacturer. Micro Four Thirds is becoming increasingly popular as well and these cameras have a 2x crop factor. You should refer to your camera manual if your not sure what you have, however the Math works like this.. 500 / (24x1.6) = 14 Seconds where 24 is the focal length of your lens and the 1.6 is the crop factor of your sensor. In this example, your exposure should be no longer than 14 seconds for dead sharp stars in the resulting image.

* It must be noted that The 500 Rule is rough recommendation, and a simplification for minimizing star trailing and or maximizing light gathering. There are additional factors other than just focal length that affect the amount of star trailing you will see when photographing the night sky. These factors include sensor size and resolution as well as where the camera is pointed in the sky relative to the celestial equator (declination) however the 500 Rule will get you 95% the way there. If you would like more information on this then please do get in touch.

Back to Article IndexWhere To Shoot, Location & Light Pollution

The further you are from light pollution the more meteors you will see. If you are not in the UK or are simply interested to see how much light pollution your town and city has then the recommended resource has to be http://www.lightpollutionmap.info. Regardless of your location, photographing the night sky is far easier if you can shoot in areas where the light pollution radiance is lower than 1,00 to 3,00 on the overlay provided by http://www.lightpollutionmap.info. I try to shoot from locations that have interesting foreground subjects also, such as a monument, building or landscape, as these can really add that additional interest to the images you will produce and the photographs you will capture.

When shooting in the the UK there are now an ever increasing locations that have been awarded dark sky status, shooting a meteor shower from any of these locations will produce some fantastic results.

17 UK Dark Sky Discovery Sites

- Cairngorms National Park – The Crown Estate’s Glenlivet Estate

- The South Downs National Park – Devils Dyke

- The South Downs National Park – Birling Gap

- The South Downs National Park – Ditchling Beacon

- The South Downs National Park – Iping Common

- Suffolk - Westleton Common

- North York Moors National Park – The Moors National Park Centre in Danby

- Bristol – Troopers Hill

- Pembrokeshire Coast National Park

- Pembrokeshire Coast National Park – Poppit Sands Beach

- Pembrokeshire Coast National Park – Sychpant PCNPA Picnic site

- Pembrokeshire Coast National Park – Skrinkle Haven PCNPA picnic site

- Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – Slaidburn Visitor Car Park

- Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – Gisburn Forest Hub

- Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – Beacon Fell Visitor Centre

- Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty – Crock O’Lune Picnic site

- Brecon Beacons National Park

Tips & Tricks

When trying to photograph a Meteor shower there really inst any hard or fast rule on where you should point your camera. Meteors will be seen streaking across the sky in all directions, however, if you draw a line backwards from where they came from, this line will always point back to the radiant point or constellation the meteor shower is named after.

To increase your chances of catching more meteors it's a good idea to shoot continuously 10-30 secs at a time. If your camera doesn't have any built-in interval functionality then you can quickly and easily pick-up a cheap intervalometer from Amazon (I have done the hard work for you here > http://amzn.to/2DmIYEy). There is really no need to spend a lot of money on one as cheap models are just as suitable. Just leave a 2-second interval between shots to allow your cameras sensor a little time to cool down between exposures and to make sure your camera has enough time to save the previous image to the memory card (I would also recommend turning off your in-camera noise reduction, HDR functionality etc. to get the interval as low as 2 seconds).

Always set your lens to infinity, and arrange your composition, you may wish to do this prior to night fall and then switch your camera to manual focus, however there are several ways to focus your lens at night if your camera has built-in live view or not. If you would like to know more about this please do get in touch.

Once you've got your camera set up and taking continuous shots (exposing continuously 10-30 seconds per shot) you can relax enjoy the show. In order to save yourself from neck ache I would highly recommend taking a camping roll mat to lay down on or a reclining chair. This will allow you to look up into the night sky, whilst your camera proceeds to fire shot after shot. Don't forget the nights even in spring and summer are often chilly, so make sure you bring a hot drink and some warm clothes. In order for you to see the show at its best, you also need to allow your eyes to adjust to the general dankness, try to avoid any bright lights or looking at your mobile as this will spoil your low light vision. Also, if there are other photographers or stargazers they will appreciate you consideration in not shining a bright light around the place. If you need to see what you're doing or need to make an adjustment to your camera settings try and use a red light as this won't degrade your night vision to much. Most of all, enjoy what the night sky has to offer!

Should you have any additional pointers, comments or question please do Contact me. I'm more than happy to share my experience and knowledge with my readers, please if you haven't done so subscribe to my Newsletter using the handy form below, this will give you priority access to new images produced, special offers, news and Photography Workshops I'll be running in the upcoming months, I would also appreciate if you could share this page on your social media accounts and if you know someone who would be interested or benefit from this information please tell them about it.

All the best and good hunting.

Regards Geoff Moore

Leave a comment